This document provides a translated transcript of an episode from “The Source,” a renowned Israeli investigative TV show, examining the research of Dan Ariely. We have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of this translation, but in the event that you spot any errors or inaccuracies, we welcome and appreciate your input. Please leave your comments in this Google Doc. We value your vigilance in helping us maintain the highest standards of accuracy and transparency in our work.

Disclaimer: This document contains a translation of the original television show, prepared with the greatest possible care and professional standards. However, the translator and the poster accept no liability for any inaccuracies, errors, omissions, or misrepresentations that may occur in the translated text.

The contents of the television show, as transcribed and translated, are provided for informational purposes only. They do not represent the views or opinions of the translator or the poster. The program’s content, which includes any statements or allegations related to a scientific researcher accused of dishonesty and fraud, originates solely from the original television broadcast.

The translated transcription should not be used as a basis for legal action or judgement. Any and all claims, disputes, or controversies should be directed to the original creator, broadcaster, or any individuals or entities associated with the production and distribution of the television show.

The translator and the poster expressly disclaim all liability for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential, or exemplary damages resulting from the use of the translated transcription, or from the use of information contained therein. Use of this translation is at the reader’s own risk.

By proceeding to read or use this translated transcription, you are confirming your understanding of, and agreement to these terms.

Transcript

Professor: Eh, good afternoon. During the experiment we will be doing, you will write the last two digits of your ID, is it clear?

We took 64 students. We asked them to write the last two digits of their ID.

This is the best chocolate you’ve ever tasted.

We presented them with six different pieces.

French wine, but premium.

Narrator: The same pieces that were in Dan Ariely’s experiment?

Professor: The same pieces that were in Dan Ariely’s experiment.

Dan Ariely: We have this feeling that we are in control and we are making the decisions that its very hard to even accept the idea that we actually have an illusion at making a decision rather than an actual decision.

We came to a big class of students and asked them all to give us there last 2 digits of their social security number, so in my case it will be 79, and then we asked them to write that number next to each of the products. Wine bottles, there were computer parts, there were books, there were chocolates. And then we asked them to bid in an auction on each of those items, any price that they would pay.

Narrator: This experiment by Dan Ariely, which was considered a scientific breakthrough, produced amazing results. The students whose last digits in their ID were a higher number, offered to pay higher price for the product. Here’s more proof of Ariely’s famous motto, human beings are not rational at all.

Professor: Now, the last thing you need to do, is to write down the maximum amount of shekels you are willing to pay for each item.

Narrator: Professor Erez Siniver checks if the students in the miclala lemnihal will agree to pay more for the items, just because of the high numbers in their ID. Will the amazing results that Ariely published will repeat themselves?

Speaker: Two weeks ago, Dan Ariely’s experiment blew up, and there was a lot of noise. Ariely’s experiment from 2012. The data in his study are false.

The data in Ariely’s study could not be obtained, except if it was fraudulent.

Narrator: This news that blew up last August sounded like a crazy irony. Ariely’s experiment, which presented amazing data about how people lie, was in itself a big lie.

Professor: We read an article that says these data are fake. It’s sad, because fake data is the edge, the edge of the spectrum.

Kineret: Data faking is probably the biggest felony in science. It’s a very, very serious lie.

Professor: There is a difference between manipulating data, and faking data. And here, he says that the data are fake.

Narrator: The data were fake, but for more than a year, the biggest mystery has yet to be solved, who faked them?

Yosi: Dan, in my opinion, Dan is an honest man and I don’t believe he fixed data. Who faked them? We don’t know.

Guy: It doesn’t look good. There’s nothing to say. It doesn’t look good, but I know Dan. I was involved with him in many, many studies. There was not a single thing he did that made me underestimate his professional, ethical, and moral behavior.

Narrator: When you heard this story, were you surprised?

Omer: Look, I was surprised, yes, but it didn’t make me, let’s say, super surprised. In my opinion, he’s a bit of a dangerous person.

The moment you find something like this, it means you need to check.

Narrator: In the last few months, we checked several of Ariely’s most famous and influential studies. We talked to researchers who worked with him, we did the same experiments he did, dived into the data, and we asked Ariely dozens of questions, trying to understand whether the fake research issue was a one time and by accident, or just the tip of the iceberg. We found many more question marks, and also quite a few interesting things. Our original research brings new discoveries tonight, and reveals the truth about the work of an Israeli dishonesty researcher who has become an international star.

Speaker: Please welcome Dan Ariely.

Dan Ariely: So, I want to talk a little bit about dishonesty.

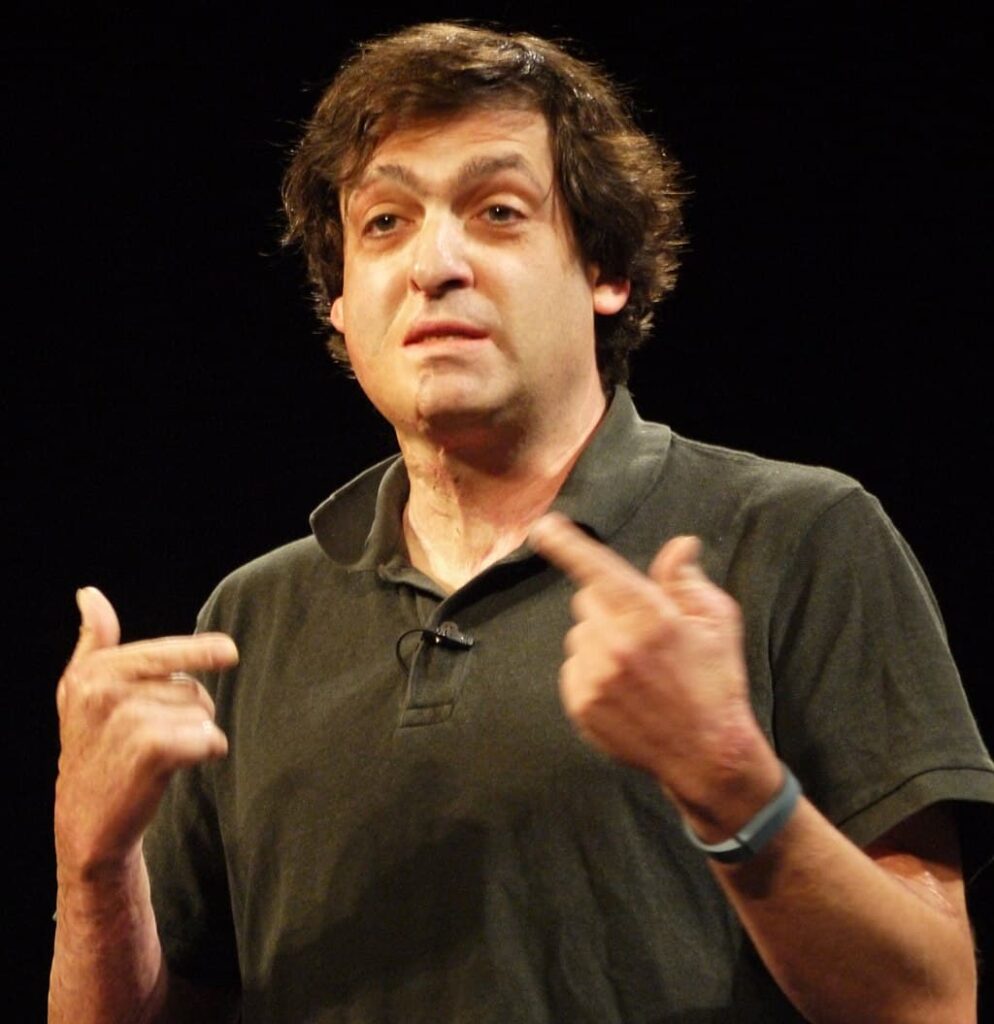

Narrator: Dan Ariely’s climb to the top of world academy was meteoric. At the age of 30, he was already a professor at MIT, a leading researcher in the field of economic behavior.

Dan Ariely: Behavioral economics doesn’t assume that people are rational. Instead, our model of human being is more like this.

Narrator: A kind of combination of psychology and economics that seeks to reveal how people really behave.

Dan Ariely: In standard economics, you look at the world, and you say, that’s the outcome of about 8 billion rational people. That’s what we can achieve. In behavioral economics, we say, no, no, no, the world can be much better. If we understand the deep mechanisms of why we fail and where we fail, we can actually hope to fix things. Thank you very much.

Narrator: There are a million researchers, but is one Dan Ariely. What made him the most famous researcher in this field in the world?

Guy: The first reason is that Dan Ariely knows how to take very complex phenomena and analyze them in a very creative way that people can understand and identify with.

Dan Ariely: For example, we sold people pain medication.

Narrator: Ariely deals with the influence of drugs on us, dating.

Dan Ariely: We got a lot of data from an online dating company.

Narrator: Understanding sexual intercourse.

Dan Ariely: We went to a night club. We asked them to rate each person how much they think he is attractive sexually.

Narrator: He knows how to talk about golf.

Dan Ariely: So we did a study about 12,000 golf players.

Narrator: we doubt there is a subject in the world that Ariely is not able to give an interview about and share his tips. Not just like that, but as a scientist who studied the subject.

Speaker: Have you ever thought about the great appeal that there is for young women in all kinds of age groups, for singers?

Dan Ariely: So yes, the truth is that I thought about it.

Speaker: And Dan, I wanted to start off with a really simple question. What do women want?

Dan Ariely: Hahah, It’s kind of…

Narrator: Everything is done with a sense of humor and confidence.

Dan Ariely: If you ever go bar-hopping, who do you want to take with you? You want a slightly uglier version of yourself.

Narrator: He always leads to a new and enlightening conclusion.

Dan Ariely: We could design a better world, and that, I think, is the hope.

Guy: He has a lot of important findings. Theoretically and practically, they are breakthroughs.

Dan Ariely: When we remind people about their morality, they cheat less.

Yosi: His research is excellent. I think he would’ve gotten to a Nobel Prize. He has a special story about what happened to him, and about his wound at younger age.

Dan Ariely: My interest in irrational behavior started many years ago in the hospital, I was burned very badly, and if you spend a lot of time in the hospital you see a lot of types of irrationality.

Narrator: In 2008, Ariely uses his insights from the hospital and from the list of studies he has done since then to write a book that takes him from a prominent name in the academy to a celebrity.

Speakers: New York Times Best Seller, Predictably Irrational. His latest book, Predictably Irrational.

Narrator: The book is translated into dozens of languages, sells millions, and also makes Ariely a sought-after advisor to governments and company managers. In the highest positions there are.

Interviewer: What do people like President Andrew and Bill Gates want from you? You’ve met them, right?

Dan Ariely: Yes.

Interviewer: More than once, by the way?

Dan Ariely: Yes.

Professor: He’s invited to prime ministers all over the world, endlessly.

Dan Ariely: I worked with the governments of Holland and South Africa, and of course the American government.

Narrator: Remember, he is known as a number one expert on lying and deception.

Dan Ariely: So if you think about it, we lie a lot.

Speaker: Professor Dan Ariely decided to check the root of L. I. E. (Shin Koo Fresh).

Dan Ariely: The reason people lie is that they lie at a level that is comfortable for them, so they can still think of themselves as honest people.

Interviewer: Okay, good. And do you lie?

Dan Ariely: I’m also a liar. Okay.

Interviewer: Give us the maximum level of honesty you can give us in this interview.

Dan Ariely: Do you want me to tell the last time I lied, or one of the greatest lies of my life?

Interviewer: What bothered you the most?

Dan Ariely: What bothered me the most…

Interviewer: Ok so no, maybe tell us the biggest lie in your life?

Dan Ariely: To look at dishonesty, we have to come up with a method to quantify dishonesty.

Narrator: Here are Ariely’s most cited studies. That is, the most influential and thought-provoking. In first place, an article describing a series of experiments that examined why and how people lie.

Dan Ariely: So, like we usually do, I decide to do a simple experiment. Here’s how it went. So if you were in my experiment, I would pass you a sheet of paper with 20 simple math problems that everybody could solve, but I didn’t give people enough time. When the five minutes were over, I would collect them back, and I would pay you by your performance. It turns out the average students we tested solved about four of these problems, and we paid them four dollars. Then for another group, when the five minutes were over, we said, please shred the piece of paper and tell us how many questions you got correct. Now, interestingly enough, people solved seven problems. Of course, they didn’t become smart, they just cheated.

Narrator: The students who shredded the pages, says Ariely, used the fact that they weren’t checked to get more money. But surprisingly, despite being able to say they solved all 20 questions, they preferred to lie just a little.

Dan Ariely: On the one hand, we all want to look at ourselves in the mirror and feel good about ourselves, so we don’t want to cheat. On the other hand, we can cheat a little bit and still feel good about ourselves.

Erez: This goes against the entirety of classical Economics, against even the famous scientists who won Nobel Prizes, where, if there is no chance that they will catch you, you lie as much as you can.

Shaul: These studies showed us that this is not the case, that there are many, many people who don’t take the money that is given to them on the table. No one can catch them, and they don’t take the money.

Narrator: His conclusions were very surprising.

Professor: Yes.

Narrator: Professor (?) doubted Ariely’s theory, and he decided to test it with a new experiment. He gave his test subjects 20 math problems, similar to Ariely, but with one significant difference.

Professor: They do it at home, without anyone seeing how much they really did. This is a sterile environment.

Narrator: And they measure the time for themselves?

Professor: And they measure the time for themselves, and they see 5 minutes, and no one sits on their heads.

Narrator: What were the results?

Professor: 80% lied, and those who lied, lied a lot. That means that, our conclusion was that if you lie, you don’t lie for 6 or 7 problems, you will lie all the way. If the environment is an environment that you think is safe, without any risk of being caught. These are completely opposite results from what Daniel Ariely received.

Narrator: So who is right? During the Corona period, we he had a rare opportunity to test whether in reality people really behave according to Ariely’s famous theory.

Speaker: From now on, exams at universities no longer take place in the campuses, but through the Internet, in an online way. And this, for example, is what happened in the michlala leminhal.

Professor: When you do an exam at the campus, the average was 60 in the course.

Speaker: When the students open the exams home alone, without supervision, they have made the task of cheating to a riskless job. The scores went up to 90-95. That means, people lied a lot.

Narrator: A larger study is required to reach significant conclusions in the matter, but in any case, so far, it is a legitimate academic problem. But this story has also reached a much more problematic place. This happened when Ariely decided to turn the experiments that made noise at the academy to a hot product in the general public.

When he’s promoting a new book…

Speaker: A book, the truth about the truth, how to cheat everyone all the time, and still stay happy.

Narrator: Ariely talks again and again about the lie test and the shredder.

Dan Ariely: Who here cheated at least once in 2013?

Narrator: But this time it is a modified and sophisticated version of the test.

Dan Ariely: What people in this test do not know is that we played with the shredder. Talking about dishonesty. What people in the test do not know is that the shredder was “fixed” by us. The shredder only shreds the sides of the page, but the main body of the page remains intact. So when you put it in, it vibrates, it shakes, it makes the right noise, but the main body of the page remains intact. If you put the page in, you would feel that it is vibrating, and there is noise, and everything looks good, but the page remains intact.

Narrator: This is much more than a funny anecdote. In the previous version of the experiment, Ariely could only estimate how many people that took the test averagely lied, but thanks to this fascinating trick, Ariely could know exactly who lied, and how much he lied.

Dan Ariely: And because of this, we can know how many people really lied.

Narrator: This is much more important research, with much more impressive findings.

Dan Ariely: In total we ran this experiment with about 35000 people and from this 35000 people there were 20 who were big cheaters, we also found 25000 little cheaters.

Narrator: There is only one problem. It is not certain that all this really happened.

You specialize in research in the field of “cheating”. Have you ever seen an academic work where the participants were being deceived? Have you ever seen such a thing?

Professor: Good question. I can’t tell you.

Narrator: We will tell you. Ariely talked about this experiment endlessly in the media, but he never published it in an academic paper. This is very surprising. In the academic world, such important works are almost always published. When we turned to Ariely, he insisted the experiment was indeed conducted at MIT.

Dan Ariely: The shredder shred the side of the page but the main body of the page remained intact.

Narrator: But when we turned to a researcher who worked with him on the experiments of lies and shredders, he did not mention any practice with a shredder that does not shred.

Did you participate in any experiment where the page was not really shredded?

Professor: No, no. In our experiment, it was really shredded, and we were not allowed to know what each person really did. We could only present the result in general.

Narrator: So what do we have here? Ariely presented in the media and in lectures an exciting experiment with a shredder that does not shred, which led to a lot of exciting discoveries, but it was not published in the academy, and prominent researchers in the field do not know anything about it. More than that, when we asked Ariely to provide elementary details, such as who worked with him on the experiment, and when exactly it was conducted, he replied that he does not remember. Could it be that Ariely does not remember such details about an experiment on which he worked and gave interviews about for years? And if this is not a matter of memory, could it be that Ariely invented a story about an experiment that has never been conducted?

Speaker: Today, Dan Ariely on irrationality at the dentist’s office.

Narrator: To try to answer this question, we checked another interesting story of Ariely.

Dan Ariely: So imagine you came to a dentist, you got your x-ray, and then we took your x-ray and we also gave it to another dentist, right? And we asked both dentists to find cavities, and the question is, what will be their agreement? How many cavities would both people find in the same teeth? It turns out, what Delta Dental tells us, is that the probability of this happening is about 50%. 50%! 50%!

Narrator: Delta Dental is a medical insurance company in the United States.

Dan Ariely: 50%! It’s really, really low. It’s amazingly low. Now, why is it so low? It’s not that one dentist finds cavities and one doesn’t. They both find cavities, just find them in different teeth.

Narrator: Again, a great story, full of humor, but again, is it real? Another researcher, who was present in the gathering with the insurance company and Ariely, confirms it, but the insurance company denied everything. “Ariely can’t quote us because we don’t collect such data”. Ariely had to admit: “they didn’t give me the data. It’s just something they told me at the company.”

Despite this, in his lectures he continues to present this data, which he has never seen before.

Dan Ariely: By the way, here is a statistic. In the us, what are the chances that the second dentist will find the same cavity in the same tooth? Its about 50%.

Narrator: But this story goes much further. In 2018, Ariely’s research center at Duke University published a study that reached the exact same conclusion. The center’s researchers examined data from Delta Dental insurance company, and the results show that when two dentists look at the same teeth, there is a 50% chance that they will reach the same conclusions.

Just for the record, this Is a complete lie. Ariely’s research center didn’t conduct any such study.

Speaker: I want to make it very clear that we never had access to that data. That was their research question not our research question.

Narrator: Immediately after we asked Ariely for an answer to the fake experiment, he asked to delete it from the network.

Dan Ariely: It tuns out that Jekyll and Hyde is a much better description of ourselves then we usually think.

Narrator: The next experiment is described in a full chapter in Ariely’s book, and it’s also one of his most famous studies.

Dan Ariely: We took a group of students, in what we call a cold state, a state of non-arousal, and we asked them questions about their sexual preference. We excepted them to be conservative in their sexual preference and they were. But then we gave them a laptop with some pornography and we asked them to get themselves to a certain level of arousal, and when they got to a certain level of arousal the same questions begin popping up. In the cold state, they said I would never do this, I would never do that. In the hot state, they were much more likely to see themselves behaving in this way.

Narrator: The data presented by Ariely were truly sensational. For example, in a state of sexual arousal, a small number of the testers said that they can see themselves getting attracted to little girls, getting aroused by shoes, and even, to a certain extent, getting aroused by animals. Several university researchers realized that something was very strange here. We talked to one of them, a senior researcher from an important European university.

So I understand that something seemed strange to you, what exactly did you do?

Speaker: We started looking into exactly what happened in the study. In fact, the study is really, really weird. To give students laptop to masturbate, it was unheard of.

Narrator: To find out how strange this business is, according to Ariely, his testers managed to answer about 20 different questions on the computer while they were masturbating on the verge of orgasm.

Speaker: The data is unlikely. Actually, impossible You can’t give it the benefit of the doubt.

Narrator: We also checked with Israeli statisticians, and they agreed. There is a mistake here. The data is improbable.

Speaker: there is no record of the study ever been conducted. I know someone who asked MIT for the record of this and he got no response. But I will suggest if you want to pursue this, I would advise you will make a request and just verify it for yourself.

Narrator: So we asked MIT, the university where Ariely worked at the time, if they gave permission for this experiment. We didn’t get a response.

Speaker: So people also called UC Berkeley, no records.

Narrator: Ariely claimed that the experiment was conducted at UC Berkeley, which is in California. So we asked Berkeley, and there they told us that they didn’t know about the experiment.

Speaker: So the whole package seemed extremely unlikely. If you read the description of the study, you will see a research assistant named Mark. If he will say he doesn’t know the guy that he wrote about in his book, then, yeah…

Narrator: So we asked Ariely: Who is Mike? What is his full name? He also chose not to answer.

In conclusion, another colorful and fascinating experiment, which might not have taken place, but Ariely refuses to provide any evidence that it did. Also in Israel, researchers from Technion decided to check the results of one of Ariely’s most well-known studies.

Interviewer: This is a very famous study, which shows that signing an ethical agreement at the beginning causes people to cheat less than if you sign it at the end.

Dan Ariely: We did a study with a big insurance company. This is an insurance company that sends people a letter asking them how many miles they drove last year. Now if you got one of those letters, do you want to increase the number or decrease it? You want to decrease it because your premium would get lower. We got some people to fill the odometer reading and then sign at the bottom, and some people signed first and then filled the odometer reading. And the people who signed first cheated by much less.

Professor: The fact that you made them remember something ethical causes them to cheat less.

Narrator: These results excited governments around the world. In a letter published by the Obama administration based on Arielli, adding a signature at the beginning of a files where people and businesses are required to report their incomes might lead to more accurate reports. The British government also quoted Arielli in an official letter. And in general, many governments and organizations tried to implement his discovery to fight tax frauds, insurance and what not.

Professor: But in 2020, it turned out that the data of the experiment couldn’t be repeated. People in other labs found that the signature location does not really affect the cheating amounts.

Narrator: The researchers at Technion developed a new experiment that sought to understand what’s actually going on.

Speaker: In the experiment, 280 test subjects from all over the world participated.

Professor: We asked people to read stories and we told them that it is very important for us that they read the stories to the end and if you do not read them to the end, we will not pay you.

Speaker: We tell them to sign. “I understand that I need to read all the stories to the end.” They do the same thing at the beginning or at the end.

Narrator: The test subjects were asked questions about the stories and according to the answers, the researchers evaluated whether they really read them or cheated. The researchers concluded that everything depends on the circumstances. In certain situations, the location of the signature reduces the chance to cheat.

Speaker: When will it work? When it is clear to the person that he might get caught.

Narrator: But in other situations, really not.

Professor: If you know that it is impossible to check whether you signed at the beginning or at the end, it does not matter.

Professor 2: Yes, getting the same data as in previous experiments is a very, very important thing. That is, you see that different groups of researchers tried, succeeded in getting the same result. Again and again and again. Again and again and again.

Narrator: Did you hear about repetitions of this experiment with the signatures that succeeded?

Professor: No.

Dan Ariely: By the way, we have replicated it in all kinds of ways.

Narrator: For years, Ariely has claimed that his revolutionary experiment has been successfully repeated more than once.

Dan Ariely: Including with taxes in a country in South America and including with traveler insurance in Northern Europe.

Narrator: What a country in South America, what a company in Northern Europe? In this case, we again asked Ariely questions. We asked the details of the successes that he was so proud of. Again, he answered that he does not remember.

Professor: If the result is received in a systematic way, in another experiment and another and another, and always in a consistent way, we get the same result. You can say, yes, this is real. This is how people behave. On the other hand, if you see it in one experiment and not in others, you did not succeed in repeating it, then it means that it was either randomly accepted or accepted because data faking or some fraud. These are the two possibilities.

Narrator: Last August, it became clear why the many repeated experiments did not succeed. The research that so many scientists, governments and corporations around the world, was actually no more than a hoax. The data that Ariely presented to everyone were simply fabricated.

Interviewer: The insurance company fabricated the data. So they will line with the research hypothesis?

Dan Ariely: I have all kinds of hypotheses about what it could be.

Narrator: Those who are on Ariely’s side are convinced to this day that all he did in this case is a mistake made by accident. Or in the least? Negligence.

Speaker: After the case exploded, I called him and told him, Dan, I know you, I have no doubt that there was no fault in your behavior. Even if there were professional errors, nothing was done on purpose.

Speaker 2: When a friend is in distress, I think friends should stand by him.

Interviewer: That didn’t really happen?

Speaker 2: No. A lot of people ran away from the ship because they thought it was sinking.

Narrator: We are advocates of friendship, but when it comes to science, credibility is also important. And in this test, the explanations that Ariely gave for what happened here are not really valid.

Dan Ariely: I was part of the research team. I didn’t look deep enough at these data.

Narrator: In an interview with the newspaper Haaretz, Ariel claimed: “the errors surprised me. I didn’t look at the data. That is, someone else in the research team was supposed to notice the fake data.” But when we returned to the original article in which the experiment was published, there, Ariely claims the opposite, that he analyzed the data. That is, at least in one of the versions, Ariely did not tell the truth.

Speaker: Good writers can say, we only publish very interesting and innovative things. When you make up the data, you can make up anything.

Speaker: So the pressure is huge. People can’t stand under this pressure. And then the incentive to lie is very high.

Speaker: If you need to collect the data, it takes a time. If you made up the data, you have a made article. You don’t need to collect them.

Professor: You can’t come and say, he needed this article to get the professor title, or he needed this article to raise his salary. He already had these things. He didn’t have anything to gain from this.

Dan Ariely: Hi, my name is Dan Ariely, and I’m the Chief Behavioral Officer at Lemonade. When we deal financially with people that we like, care about, and trust, there’s a good amount of room for improvement.

Narrator: It’s true that Ariely has reached the top of the academy a long time ago, but another publication never hurts, and Ariely knew how to translate it into a lot of money.

Speaker: A new application. Professor Dan Ariely, he’s one of its founders.

Speaker: A new app that promises to help manage your time efficiently.

Speaker: Google, and no other, purchased his application for tens of millions of dollars.

Dan Ariely: Hi, my friends from IBI, this is Dan Ariely. I want to tell you with lots of excitement about a new idea.

Narrator: Five years ago, he started to appear in the media as a kind of investment guru, who can teach all of us how to get rich.

Speaker: Ariely came up with a surprising index regarding the worthwhileness of an investment in companies. He knows, if a company will succeed, according to its work conditions, pensions, the quality of the furniture, even coffee.

Dan Ariely: It’s crazy. What does it mean? It means I can invest, without looking at quarterly reports, without looking at annual reports.

Narrator: All you need, Ariely explained, is to invest in companies in where the employees are satisfied.

Speaker: So you made a new index.

Dan Ariely: I founded a new index.

Narrator: His index, Ariely claimed, it did better than the S&P index, the big companies index in America. The problem is that the data that Ariely presented were not very consistent. In this commercial video, for example, he talked about impressive returns.

Dan Ariely: It’s about 6.5% per year above the S&P.

Narrator: But in this interview with Dani Cushmaro, on the other hand, he already talked about a profit that you wouldn’t even dream of.

Dan Ariely: If you were investing a dollar in the S&P in 2006, you would have about 3 dollars in 2017. If you were investing a dollar in my index, in 2006, you would have almost 9 dollars.

Narrator: So far, we have talked about theoretical models that Ariely presented, not about investments. But in 2018, Ariely offered the Israeli public to invest in a special fund called the Dan Ariely model. Many were impressed and invested in the fund more than 100 million shekels.

You saw the results of the fund. What were the results in the end?

Professor: Ariely’s fund did not manage to break the index. In fact, it achieved lower rates for investors. For example, people who invested in his index were supposed to get a higher rate of return. On the contrary, the investors in his fund were exposed to more risk and received a lower rate.

Interviewer: Do you need money to help the government?

Dan Ariely: Yes.

Interviewer: The Finance Ministry?

Dan Ariely: Yes. In the end, I want to help the citizens, not the Finance Ministry.

Narrator: In the past, Ariely volunteered to advise the Israeli government in a few matters.

Speaker: I want to say thank you to Dan Ariely.

Narrator: But during this interview in 2019:

Dan Ariely: I’m not only volunteering, I also finance these moves.

Narrator: He had a good deal with the The Finance ministry.

Professor: The budget department thought it needed some serious behavioral economist that could provide some insights. And it turned to Dan Ariely because Dan Ariely is a very, very well-known and out-going person in this field.

Narrator: According to the data that we examined, Dan Ariely’s budget for the Finance Ministry was 17 million shekels in four years. Is that a lot?

Professor: That’s a lot. In general, a very large amount. In general, consulting companies do not take amounts that are close to this amount. 17.5 million shekels in this context is a huge amount.

Narrator: In other words, this is an amount that buys a serious amount of work.

Professor: A very, very massive and very large amount of work that you need to hear about.

Narrator: In practice, we didn’t hear about it too much, and both Ariely and the Finance Ministry refused to answer this claim. We were able to get our hands on three items that the Ariely’s company submitted to the Finance Ministry. One of them was a recommendation to improve the government offices’ dedicated services. For example, note this recommendation to make the webpage compatible with cellphones. The other two items provided solutions to reduce traffic jams on the roads. Most of the solutions were not implemented, and the roads in Israel… Well, you know their situation.

Interviewer: You were the Chairman of the National Economy Board and the closest economic advisor of the Prime Minister in all four years in which Ariely was the advisor to the Finance Ministry on economic matters.

Professor: That’s right.

Narrator: Did you know if his appointment led to some economic process?

Professor: No.

Dan Ariely: When the coronavirus began, I received a request from government offices to come and help, so I showed up.

Narrator: When the coronavirus crisis broke out and everyone was clueless, Ariely came from America with a special original idea that he described in a recent interview to yedihut ahronot. He advised the head Aka to infect a military camp in Corona.

Professor: He proposed this not to provoke, and not to harm the soldiers. He proposed this because he really thinks that from a scientific point of view it is the right way to get scientific data on a contagious pandemic that you don’t have enough knowledge about.

Narrator: After the headline made a fuss, Ariely claimed that in the article they didn’t understand his meaning.

Dan Ariely: They didn’t quote correctly. There was a group that turned to me and asked me to volunteer. I turned to the army to get the place to conduct the experiment.

Narrator: Interesting. But that’s not what head of Aka remembered. The man who received the proposal from Ariely.

Moti Aka: What? He asked me to do an experiment with the help of soldiers. A large military base. If I remember correctly, it was tens of thousands. I told him that there’s no chance.

Dan Ariely: Now, if we make flawed decisions and we have good, bad intuitions about them, what can we do? And the only answer is experiments.

Narrator: Back to Ariely’s academic experiments. And now, to the most fantastic story we’ve discovered.

Dan Ariely: One of the experiments we did, for example, was to ask people to remember the Ten Commandments.

Narrator: In this experiment, the number one experiment in his most famous and influential article, Ariely didn’t stop talking about for years. Like in his previous experiments on liars, Ariely gave the test subjects a math test. He asked them to repeat how many exercises they answered correctly. But this time, before that, he gave them another small task.

Dan Ariely: We asked half the people to recall ten books they read in high school, and we asked the other half to recall the Ten Commandments. Then we tempted them with cheating. Interestingly enough, those who were asked to think about the Ten Commandments, nobody cheated.

Narrator: Amazing. The memorization of the Ten Commandments didn’t diminish the cheating, but completely annihilated it. All the test subjects told the truth.

Dan Ariely: Those people who tried to recall the Ten Commandments, given the opportunity to cheat, did not cheat at all. After we asked them to try and recall the Ten Commandments, nobody cheated. Just contemplating the Ten Commandments eliminated cheating. They stopped cheating. Nobody cheated.

Narrator: Nobody cheated. This is an experiment that possibly found a way to eliminate cheating. Do you know this experiment?

Professor Erez: I’ve heard of this experiment, and I’ve heard it many times, but it’s hard for me to believe the results. This result can’t be true.

Narrator: So we turned to Professor On Amir, Arieli’s partner in this experiment.

On Amir: We launched this experiment in 2002.

Narrator: It’s hard to believe, but it turns out that the results that Ariely presented over and over again over the years were never received in any experiment.

Narrator: You don’t know about each and every one of the participants, whether they cheated or not?

On Amir: That’s right. But that’s not what we’re saying. We say that on average it reduced cheating. We can only talk in general about the group.

Narrator: I understand. So we can’t say about all the members of this group that no one cheated?

On Amir: No, not at all.

Narrator: It turns out again that the stories of Ariely the interviewee, the professor, the performer, are not exactly true to the facts.

Dan Ariely: Nobody cheated.

Narrator: But in this case, Ariely’s findings were also a big question mark.

Professor: When, after 10 years, a group of researchers launched this experiment in many countries and checked the results, what they found was that the findings didn’t repeat themselves.

Narrator: In their experiments, the attempt to remember the 10 Commandments had no effect.

Professor: Yes, there was no effect.

Narrator: it’s not always possible to get the same results, but here we’re talking about an extremely unusual scope. The experiment of the 10 amendments was run again over thousands of tests by 20 laboratories of researchers from prominent universities in Israel, the United States, Belgium, Holland, Portugal, Germany, Sweden, France, Turkey, Canada, and other countries. And the results that the researchers obtained were the opposite of Ariely’s results.

You wrote that you don’t trust his research findings.

Professor: Yes.

Narrator: Why?

Professor: Because he jumps to conclusions in a careless way. A person who sees research findings and jumps from them to conclusions that go too far, is a liar.

Narrator: Do you think Dan Ariely is a liar?

Professor: I think he is. I think he is.

I’m sure there were errors in the experiment.

Narrator: It’s hard to understand what exactly was in this famous experiment for a simple reason. For years, Ariely didn’t stop contradicting himself. Once he wrote that 229 students participated in this experiment, and once:

Dan Ariely: we asked 500 undergrads to try and recall the 10 Commandments.

Narrator: Once, all of the subjects received half a dollar per correct answer. And once, 2 students were randomly chosen and they were the only ones who won 10 dollars. It is not even clear when the experiment was conducted. A European researcher heard from the people of Ariely’s team that it was in 2006 and we got a completely different answer from them.

On Amir: We started the experiment in 2002.

Narrator: And we found in Ariely’s original file, it was mentioned the experiment was conducted in 2004. Confused, we tried to reach the person who, according to Ariely, had run the experiment in the field for him. It wasn’t easy, but in the end we got to her. Aimee Drolet, a senior professor at UCLA University in California.

On Amir: She was Dan’s good friend, and said, I have no problem, you can send it to me, I’ll run it for you.

Narrator: The professor told us that she doesn’t remember it, but it’s likely that as a good favor for Ariely she shared some of his questionnaires with students.

Professor: So we sent it to her, and we got back some data.

Narrator: But, she says, she’s sure that the experiment that Ariely described in his article, with the raffle, cash reward for the students, supervision of an experiment manager, and more, has never been conducted at her university. It’s claimed that the experiment was conducted at UCLA in the way it’s described in Ariely’s article, but that’s not true. According to what UCLA University told us in response, this experiment was never done at the university.

Professor: Good afternoon. In the experiment that we’re going to do, you will write the last two digits of your ID card. Is that clear?

Narrator: And what about the experiment that we tried to restore in the michlala lemnihal?

Professor: Everyone has to say about each item, if, in the price of the two digits, let’s say you got 2 and 0, that’s 20 shekels, will you buy the item, yes or no? Write yes or no.

Narrator: The fact that Ariely proved that recalling a high number will make a person agree to pay more money?

Professor: Everyone gave back the forms? What did we get? The results that we got were completely different.. The ID card doesn’t affect the decision of how much to offer for each item. Which is completely different from the results that Dan Ariely got.

Speaker: Every day, we receive thousands of results.

Narrator: The fake data report cracked Ariely’s credibility at the academy, but in the media, he continues to star. At kan11, a series he made aired.

Dan Ariely: I’m monitoring everyone’s behavior and trying to understand the mistakes we’re making.

Narrator: At the American Universal Studios, they started to produce a drama series based on his research, which is intended to be broadcast on NBC. The main character, in the image of Ariely, is a charismatic researcher, which conducts creative experiments in particular.

Professor: He’s a superstar on the public level. I think the scientific community is starting to understand that maybe it’s better not to value him so much.

Narrator: Our investigation looked at several of Ariely’s most famous experiments and research. We found experimenta with significant problems in the data.

Dan Ariely: we gave them a laptop with some pornography and we asked them to get to some level of arousal.

Narrator: An experiment in which Ariely refuses to disclose details about him and doubtfully ever happen.

Dan Ariely: What people in the experiment don’t know is that the shredder didn’t really work.

Professor: No, no, in our experiment, it was really shredded, and we were not allowed to know what each person really did.

Narrator: A publication by Ariely’s research center about research that never took place.

Laptop: I want to make it very clear that we never had access to that data.

Narrator: And Ariely’s stories about the results that were allegedly received in his experiment.

Dan Ariely: But people who tried to recall the 10 Commandments given the opportunity to cheat didn’t cheat at all.

Narrator: In fact, they were never real.

So you can’t say about all the members of this group that no one cheated?

Professor: No, not at all.

Narrator: Ariely dedicated a part of his career to the question of why people lie. What happened in his personal story? It seems that the answer to this should be found in the famous lectures of Prof. Dan Ariely.

Dan Ariely: On the one hand we all want to look at ourselves in the mirror and feel good about ourselves. So we don’t want to cheat, on the other hand we can cheat a little bit and still feel good about ourselves, so maybe what is happening, is that there is a level of cheating we can’t go over, but we can still benefit from cheating at a low degree as long as it doesn’t change our impression about or self.

Raviv Droker: Joining me is Itay Rom, Prof. Eyal Pe’er. You work these days with Dan Ariely on research.

We’ll be right back. Advertisements.

And we’re coming back. The original studio. We’re back. Good evening to Itay Rom . Good evening. And to Prof. Eyal Pe’er from the School of Public Policy and Administration at the Hebrew University. We’ll talk soon. But first, Prof. Dan Ariely’s response.

Dan Ariely: Ironically, you’re trying to call me unprofessional by means of non-professional tools. The experiments conducted by Prof. Sini Bar are non-professional restoration of my own experiments. but experiments that are clearly and essentially different in many ways. To disprove me with a completely different experiment is a provocation without a professional basis. Researchers are required to maintain data on research for five years. I have no data on research that was conducted more than 15 years ago, and I have no way to find it. I do not conduct the research alone. Over 30 years of research, I had 248 partners in the scientific department, including the most esteemed researchers in the field. Of course, if the claim is that I have made up research, you blame a huge group of academics from dozens of universities around the world, when the only evidence for this is that I have was not able to prove that I have no data. The experiment in which Professor Aimee Drolet helped, was conducted more than 15 years ago. I don’t know why she remembers things the way she described them to you. I and the other two professors who are signed on the research remember the details as they are described in the article that was published. There is a difference between academic articles and free conversation with the public. Your attempt to catch me on one word or another and to get it out of the context only reflects a desire to defame and not more. In the case of dentists, my institute blog at Duke University was incorrectly quoted, and I asked for it to be corrected. Professor Omer Moav is not an expert in behavioral science, and it is not clear why he was invited to give an opinion about my research.

Raviv: Itay, tell us a little bit about the conversation with Ariely, which doesn’t take two or three days like many times, but long months.

Itay: Absolutely, yes. We first spoke to Professor Ariely more than half a year ago. We asked to talk to him, to ask him questions in order to understand his work better. What surprised us was that for a large part of the questions, the answer was, I don’t remember, I don’t remember, I don’t know. Professor Ariely’s claim was that we were actually doing something unfair to him. We ask him about very small things from a million years ago. He does a lot of things, and he’s not supposed to remember these things, but that’s not the situation. I’ll explain why. First of all, we didn’t ask him about irrelevant things, but about his most famous experiments, which he talked about without stopping in a million places. Second, our questions were not at a very low resolution, but elementary things like, where did you perform this experiment? Who was your partner in the experiment? Researchers? Research assistants? Someone? And he also doesn’t remember things that are quite new, and not just the old things. I can say that I was disappointed, because we are used to these answers from politicians, businessmen. In science, everything is supposed to be transparent and open.

Raviv: Professor Eyal Pe’er, so you are much more experienced in this discipline. How reasonable is it, really, that a person doesn’t remember significant experiments that he performed and talked about so much in his lectures?

Eyal Pe’er: I think that we usually remember the experiments that we perform, and we remember their details, especially those that succeeded.

Raviv: But let’s say, you know, half a year has passed. I’m telling you, as a person who highly valued Dan Ariely and his work, in this half a year, to not find a single e-mail, Okay, he didn’t have to keep it. But we did research. Ten years ago, there were e-mails, but not a single e-mail, not a single paper, not a single Excel file with data, nothing.

Eyal Pe’er: This was really surprising. I can say that the practices in the world of research in the last decade have changed significantly. Today, we are in a world where the norm is to keep the data and publish them promptly, immediately after the publication of the paper. This is something that was not customary, really, ten years ago. The custom is to write the notes in advance, to submit the protocols in advance. This is something that didn’t exist, and it’s a shame that it didn’t exist. Today, we are in a better place.

Raviv: I, myself, as a journalist doing research, okay, so I too, after seven years, I think I can throw it away if I want to, because it’s impossible to sue. But it’s not pleasant to admit that you will find with me also research that I did 20 years ago, all that is in on the computer. It’s a bit unreasonable that researchers at this level have no paper trail behind them.

Eyal Pe’er: There is a very big change, I think, in the way in which institutions in the world require researchers to keep the data. from my experience, when I was at universities in the United States, I found that there is a high demand to keep the data, the protocols. For reasons of ethical research, reasons of, for example, if a subject comes, after a few years, to complain on something that was done or was not done, the institutions forums require you to keep things.

Raviv: I have to ask you something else about his claim that surprised me, but I’m not from the academy, to say that, a claim that you mentioned in some lecture, or in some public appearance, or in some book, or in some movie, that you did research, and from there it came, but it was never published in academic research. That is, it did its way only to popular culture, but not to academia. Is this logical?

Eyal Pe’er: Look, it not common, its not common. First of all, the laws in academia, our first motivation is to publish articles, and we, if we have good data and interesting findings, we will do everything in order for it to be published. But there are reasons that sometimes prevent us from publishing. Papers are sometimes declined from scientific journals. Like Dan Ariely. Also Dan Ariely, I assume that his articles were deleted here and there. In the last 15 years. I, of course, cannot tell you the answer.

Itay: It was not in this case. In this case, it was not a claim that it was declined, but it was simply not published. But I want to ask you, what scientific value, if we really see a certain experiment, when he talk about it endlessly all over the world, in the media, in lectures, wherever you want, but it was never published, it did not stand for a real inspection, it was not published academically, what scientific value does it have, if at all?

Professor: I think it is less of a scientific value. Because to do an experiment and to tell what its findings were, it remains at the level of the story, at the level of the anecdote. In order for science to be meaningful…

Itay: So I can tell what I want, right?

Professor: Also. But in order for science to be meaningful, it must first of all be a theory, it must be connected to existing literature, it must be a significant contribution to the knowledge that exists in the literature that exists today. And this happens only when you write the paper, not when you just do the experiment and then tell about it somewhere.

Raviv: Itay you probably watched dozens of hours of Dan Ariely. Yes. Dozens or hundreds of appearances of his. And we talked about it, quite a lot. I’ll tell you my impression sometimes. I had the feeling that he has the storyteller syndrome. He tells so well, he has punches, he’s funny, he’s interesting, that many times I felt that maybe he’s just wrapping up the facts so that the punch will be better, as we see with many stand-up comedians.

Itay: Look, I can tell you that many stories were not mentioned in the article that certainly created this feeling. I’ll give you an example. There is a lecture, conference he participated in England, and there he talks, as usual, about the experiments he does. And there he talks about some experiment that really shook the head of the Israeli army. The head of the Israeli army. Dan says he was so angry that he talked to him, and they sat down for coffee, and he explained his claims to him. So we checked whether Dan Ariely really met with the head of IDF at that time, chief Aluf Kochav. Did they sit down and talk about Dan Ariely’s experiments? From our investigation it turns out that no, it didn’t happen, they didn’t meet. Another thing, I can tell you about an experiment, for example, really an amazing experiment, that he talked about it in his interviews, I’ll read it to you, “we conducted an experiment in which”, according to him,” teams of five people went to the whore houses where they learned how to perform oral sex”, all kinds of things like that. It’s not something you forget, it doesn’t happen every day. I asked about it, who was in the experiment, what did they say, who? No answer, nothing.

Raviv: I want another question. The thing I noticed the most when I saw the documentary of Dan Ariely, was the broken shreder. It shook my head, I have to say. That is, it’s a way to know if a person is a liar or not a liar, and it’s such a smart trick, as if he’s lying, but he’s not lying, and it killed me that in the end it wasn’t really a part of the research, it wasn’t published in an academic journal, we don’t know if it was ever done. What do you think about this?

Professor: Yes, the articles that I saw, which are similar to this, talk about asking people to throw the paper into the recycling bin, and then take the paper back from the bin. And then a person has suspicion that they took the paper from him. That’s right, I think that in general, we often don’t believe in cheating the subjects in an experiment. It’s something that can really hurt the credibility of the next experiments. If a subject knows that we cheated him once, he will come to the next experiment, he will think, wait a minute, is everything the researcher tells me really true?

Raviv: Itai, is Ariely’s image damaged today since the publication a year and a half ago? It was a publication that you think that a person’s career will end as a result of this, but you hear, a film here, a film there, it looks like life as usual.

Itay: One of the very surprising things in my opinion is that the university of Ariely, or any other authority, didn’t come out with a clarification that gives answers to the public, scientists, and people like Prof. Pe’er, what the hell happened here, and who did it? It’s something they simply don’t answer. Everything remains closed within the family.

Raviv: But you have to say that his partner is going to publish a book, and there we can read his partner version.

Itay: His partner is going to publish a book in about a week, and I can already tell you that he doesn’t exactly think that Dan Ariely gave a clear explanation on this story. Both of them claim one to the other that they are not exactly reliable.

Raviv: Ok, Prof. Yael, Peer, thank you very much, Itay, thank you for this investigation, thank you both. You can find us all the time on the Facebook page of the source, to respond and send us messages. Thank you. After us, the zinor, good night.